STEP 4

Evaluate Climate-Resilience Attributes

In this step:

- Learn about climate-resilience attributes

- Score the fishery system’s attributes

- See the big picture of climate-resilience attributes in the fishery system

Fishers in Mexico. Photo: © Carlos Aguilera/EDF

Background

The SNAPP Climate-Resilient Fisheries (CRF) working group identified, defined, and articulated mechanisms for attributes that confer climate resilience across the ecological, socio-economic, and governance dimensions of fishery systems (Mason, Eurich, Lau et al. 2022). The group then applied this comprehensive resilience framework to examine 18 diverse fishery systems around the world (Eurich, Friedman, Kleisner, Zhao, et al. 2024). Based on that work, Step 4 of the CRF Planning Tool enables users to evaluate a set of 22 climate-resilience attributes that facilitate a deeper knowledge and understanding of the fishery system.

Ecological Attributes

Habitat Diversity and Quality

Definition: The availability, variety, and caliber of suitable habitats.

Mechanism: The ability of a species to use different habitats and the availability and health of those habitats provides flexibility in the event of degradation or disturbance of a particular habitat.

Case Studies: United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Dietary Diversity

Mechanism: Climate change may disconnect species from their prey or may reduce the availability of particular prey. Species that can consume a variety of prey may be more resilient to these changes.

Case Studies: United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Spatial Flexibility

Definition: The ability of a population to tolerate changing conditions or move to new locations to find suitable conditions.

Mechanism: Species may be resilient to ecosystem changes if they have a broad tolerance for environmental conditions and/or habitat types in a given location, or are mobile and able to shift locations to track their preferred conditions.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Evolutionary Flexibility

Mechanism: Species with high genetic diversity, plasticity, or evolutionary potential can adapt to changes more quickly, persist under novel environmental conditions, and evolve to be better suited to new conditions.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries

Stock Status

Mechanism: A plentiful population with a well-distributed age structure can better withstand and recover from short-term impacts that affect populations or specific cohorts.

Case Studies: Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery

Species Diversity

Definition: The number of different species present in an ecosystem and relative abundance of each of those species.

Mechanism: The number of species, range of life history traits, functional redundancy, and response diversity can all reflect species diversity in the community. Greater diversity confers fisheries resilience through portfolio effects (e.g., the stabilizing effect from a population acting as a group or ‘portfolio’ of diverse subpopulations instead of a single homogeneous population) that support fisher livelihoods and ecosystem functioning against climate impacts.

Case Studies: California Dungeness Crab Fishery (United States), Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery

Ecosystem Connectivity

Mechanism: Strong ecosystem connectivity and high rates of larval or later-stage dispersal enable species to find and occupy suitable habitats in multiple locations throughout the ecosystem.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Madagascar Nearshore Fisheries, Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery

Socio-Economic Attributes

Wealth and Reserves

Mechanism: Individuals and communities with more material, financial, or human resources may be able to pursue more options for adapting to change.

Case Studies: California Dungeness Crab Fishery (United States), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery

Economic Flexibility

Mechanism: Being able to rely on diverse economic sectors and activities can buffer impacts that affect any particular activity and support adaptation by re-balancing the mix of activities or supporting the pursuit of new opportunities.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries

Community Flexibility

Mechanism: When fishers and communities can change fishing locations, move between occupations, change geographies, use infrastructure for a variety of purposes, or pursue similar strategies, they have a better chance of offsetting impacts of climate change on their livelihoods and well being. However, there may be trade-offs between community flexibility and ecological resilience, for example if a fishing community depleted fish stocks in one location only to move and do the same in another location.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States),

Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries

Technology

Mechanism: Technology can help to detect environmental changes, improve the adaptive capacity of fisheries management, enhance economic outputs from the fishery, and improve the well-being of stakeholders in the system. However, new technology could alter flows and distributions of benefits and may affect the equity of outcomes.

Case Studies: Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries

Social Capital

Mechanism: Social capital comprises trust and social cohesion within communities, across different communities, and within institutions at larger scales. High social capital supports collective action and enables societies to function effectively, and as such, it can help facilitate adaptation or transformation.

Case Studies: Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries

Knowledge and Learning Capacities

Mechanism: Individuals and organizations with greater learning capacity are better able to recognize change, perceive risk, understand relationships between climate change stressors and cumulative stressors, and assess potential responses and adaptive actions. Access to a variety of information sources can also give stakeholders leverage to advocate for certain decisions and hold decision-makers accountable.

Case Studies: Madagascar Nearshore Fisheries, Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery, United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile),

Agency

Mechanism: Agency enables people to make and advocate for decisions that are consistent with their capacities and goals, thereby empowering them with greater control over how they respond to changes.

Case Studies: Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Psychological and Cultural Capacities

Mechanism: Strong resilience mindsets enable people to accept and plan for change. In addition, a strong sense of place attachment creates a higher sense of investment in the success of a community as it experiences change, but could limit resilience if changes are so extreme that transformation or relocation is needed.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Madagascar Nearshore Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan), United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Governance Attributes

Efficient and Effective

Mechanism: Effective governance supports achieving a variety of social and ecological resilience attributes, and efficient use of resources allows a system to achieve more of its goals with fewer trade-offs.

Case Studies: United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Responsive

Mechanism: Responsiveness confers resilience through short-term adjustments in management actions necessary to remain adaptive and achieve goals efficiently.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain)

, United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Adaptive

Mechanism: Adaptive decision-making helps reduce uncertainty, manage risk, and maintain or even improve system functions and services under changing conditions. Anticipating and managing possible new risks and opportunities may also be necessary for adapting to novel conditions under climate change.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, Hokkaido Set-net Fishery (Japan)

Inclusive

Mechanism: An inclusive governance system that prioritizes participation and equity lends itself to greater compliance by constituents, smoother decision-making processes, and greater social cohesion. These qualities can instill trust and cohesion to effectively implement beneficial actions as climate change persists.

Case Studies: Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), Mie Spiny Lobster Fishery (Japan), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery

Accountable

Mechanism: Accountable governance systems hold commitments to individuals and communities to accomplish system priorities. By remaining transparent in their actions and decisions, governments can enable flows of information between policy makers and community members, thereby encouraging more effective actions in response to change and reducing the risk of corruption undermining adaptive action.

Case Studies: United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, California Dungeness Crab Fishery (United States), United States Bering Sea Groundfish Fisheries, United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia)

Leadership and Initiative

Mechanism: Leadership can activate other system attributes, like social capital, to produce a common good. Leadership increases buy-in and makes self-organization more likely. Strong leaders who take initiative are more likely to respond quickly and effectively after a disruption, thereby increasing the viability of a broader range of strategies to support system resilience.

Case Studies: United States West Coast Pacific Sardine Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery, Kiribati Giant Clam Fishery, California Dungeness Crab Fishery (United States), Juan Fernandez Islands Demersal Fisheries (Chile), Madang Reef Fish Fishery (Papua New Guinea), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia)

Connected

Mechanism: An interconnected governance system that considers various voices and perspectives across scales, sectors, and governing bodies can help ensure that important trade-offs are acknowledged and that multiple streams of benefits can be optimized. However, unless this system maintains a tight network, the complexity and bureaucratic burden can sometimes inhibit action.

Case Studies: Galicia Stalked Barnacle Fishery (Spain), Iceland Groundfish Fisheries, Maine American Lobster Fishery (United States), Tasmania Rock Lobster Fishery (Australia), United States Atlantic and Gulf Migratory Pelagic Fishery, Northeast Atlantic Small Pelagic Fishery

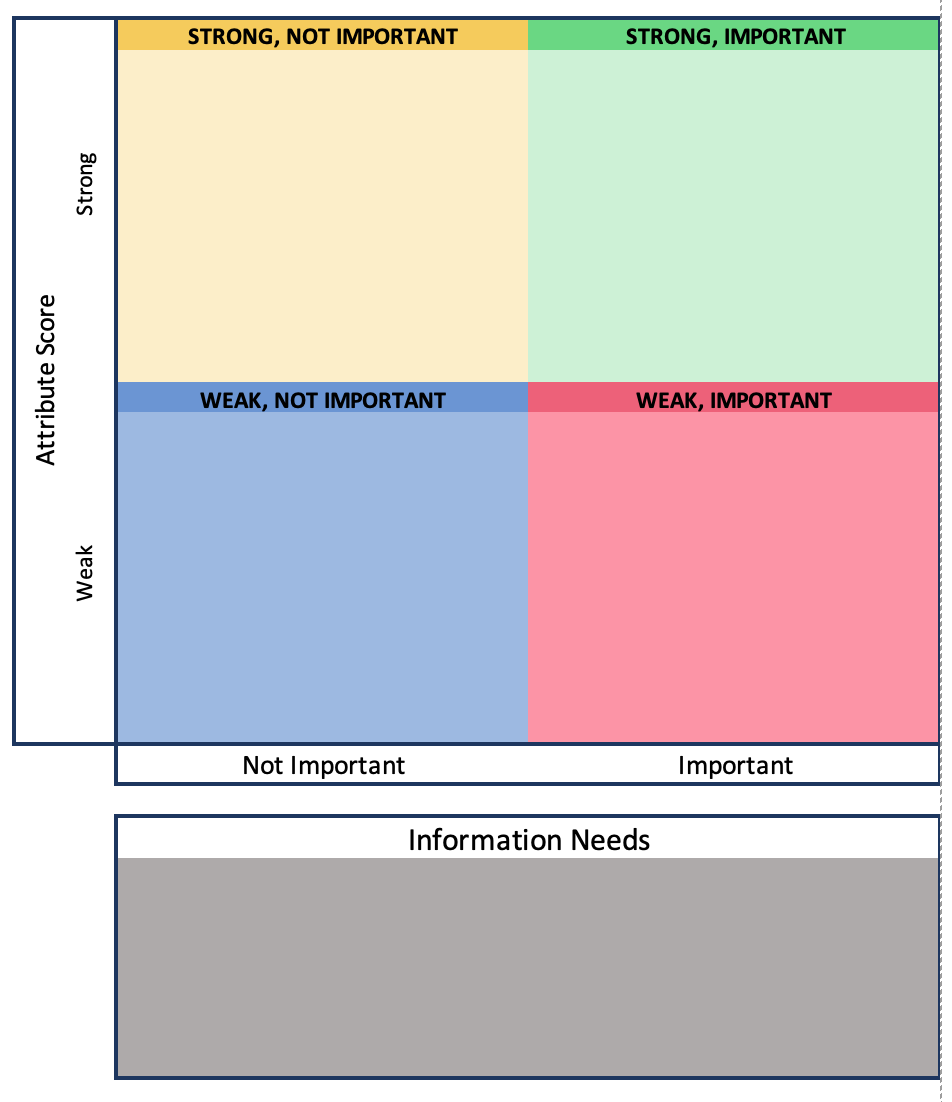

The Workbook allows for scoring of each of the 22 attributes on a scale from weak to strong (or select “Not Sure”) based on their current status in the fishery system. For each attribute, it is also possible to choose whether to designate it as important in the fishery system. Importance of an attribute can be thought about in terms of whether an attribute relates to the values, or can help address the goals and climate impacts identified in Steps 2 and 3. For example, an attribute may be scored as weak (based on its current presence in the system), but that attribute may be considered important for conferring or inhibiting resilience in the system.

This scoring process is intended to be done subjectively based on readily available information and expertise. If knowledge and information about a particular aspect of the fishery system is lacking, the tool can be iteratively re-applied as more data become available.

After the attributes in the Workbook are scored, a figure like the one below will be automatically populated to group the attributes based on their ratings in the assessment. This figure provides insights into attributes that are well established in the fishery system, as well as those that may be weak or lacking. Further, it demonstrates which attributes are perceived as important for achieving fishery goals in the context of climate change. This figure will also be used in Step 5 to help identify potential actions to increase the climate resilience of the fishery.

Attributes Assessment Figure

When the worksheet for Step 4 is completed, a figure like this one will be generated with each of the 22 resilience attributes placed in a quadrant based on its assessment scoring.

The attributes incorporated into this assessment were derived from a thorough literature review and synthesis, but they may not comprehensively represent features that confer climate resilience in marine fisheries now, or that may be important in the future. As one example, fishing practices with lower carbon footprints may be more resilient as efforts increase to mitigate carbon emissions to achieve climate goals. Users can identify and rate additional attributes that may confer resilience in their focus fishery, and we encourage you to share these additional considerations with us through the contact email.

Tasks for Workbook

In the downloadable CRF Planning Tool workbook, complete these tasks on the Step 4 worksheet.

- Score attributes based on their current status in the fishery system

- Rate the importance of attributes for influencing climate resilience in the fishery

- Review the scoring results quadrant

CRF Planning Tool Steps